Sitting on a stool in the Student Learning Centre, working quietly on her laptop, Ashley Meza-Wong is getting ready to send out a newsletter with upcoming events to members of Ryerson’s Organization of Latin American Students (OLAS). Meza-Wong is a fourth-year business management student and vice-president of marketing for OLAS. With roots in Ecuador, she uses the word Latina to identify herself, although she often uses Latinx both plurally and in situations where she’s referring to a mixed group of people. “(By using Latinx), we’re saying, ‘I am recognizing you, you are here, I see you,’” she says.

Meza-Wong is one of many Latinxs embracing the new word. Latinx, pronounced La-teen-ex, is a gender-neutral term that replaces the gender-specific terms Latina and Latino. Spanish, like many of the romance languages derived from Latin, is gendered, assuming a binary gender system. This means that pronouns in Spanish are dependent on the gender binary, specifically masculine and feminine, as grammatical genders – nouns that are assigned human male and female identifications. In fact, it’s nearly impossible to construct a sentence in Spanish without mentioning gender. For people who are gender-fluid or non-binary, there aren’t a lot of terms to describe their identity. This is why Latinx is paving the way for gender expression and identity in the Latin American community.

Latinx has gained traction in recent years for its inclusivity, especially for members of the LGBTQIA+ community. The term originated in the online queer community, but social media has helped accelerate its growth. According to Google Trends, which analyzes the popularity of Google search queries, the term spiked online in 2016. Two years later, it was added to the Merriam Webster dictionary. For many who use the word to identify themselves and others, this is a huge acknowledgment and has almost given the term the official stamp of approval. While dictionaries affect the validity of words and their meanings, it’s language that plays a powerful role in shaping our collective views as a society.

Jamin Pelkey, an associate professor at Ryerson in the department of languages, literatures and cultures, says that one of the sociolinguistic functions of dictionaries is the legitimacy they give to newly coined terms like Latinx. “Words don’t live in dictionaries,” says Pelkey. “They live in the collective memory and imagination of an entire speaking population.”

Pelkey also says that Latinx is challenging the Spanish-speaking population to think more carefully about language ideology. As a linguist, he thinks it’s important to reflect on the ways thinking patterns and language habits are interwoven. “Part of the reason it is important to move beyond simplistic binaries is that such moves allow us to acknowledge the dignity and worth of sides and everything else that falls in-between,” he says. “The middle-ground is really where most things are anyway, but we’re not very good at seeing that or adjusting to it.”

Meza-Wong believes Latinx is part of the evolutionary process of language and sees inclusivity as the premise of the term. She explains that with the creation of Latinx, we’re fighting the institutions and systems in place that may not be working for everyone. “It’s that whole ‘if it’s not broke, don’t fix it,’” she says, referring to those who oppose the change in the language. “It may not be broken for you, but it’s been broken for a lot of us.”

Inclusion is very important for Meza-Wong, but she recognizes it can be hard for people to get accustomed to the word. “When you try to incorporate something new, it’s definitely met with pushback,” says Meza-Wong. She notes that because language has developed around social and cultural change, Latinx is representing how we’re collectively choosing to approach the gender binary and gender expression. She says that for her, Latinx is also a political term. “Our identities are political. It’s an identifying term, it’s choosing how to identify.”

The feature continues after this brief audio clip, just over a minute long. In the clip, Ryersonian reporter Daniela Sosa Roque interviews Ashley Meza-Wong about the term Latinx.

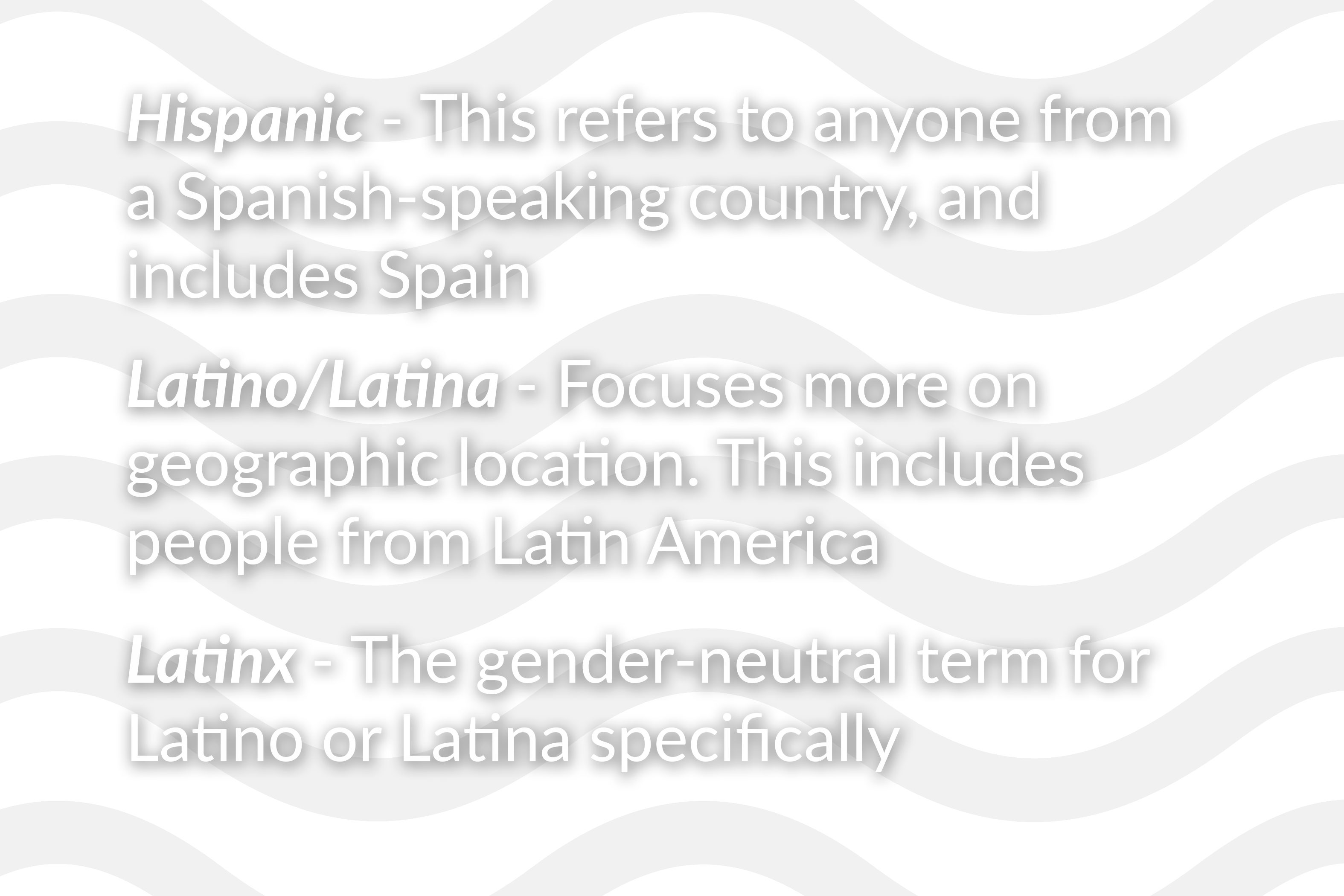

For Latinxs, navigating identity can be very complex. Some may identify themselves with the word Hispanic – a term referring to anyone from a Spanish-speaking country, including Spain. But others neglect the term because it only looks at their Spanish heritage and the violence behind colonial history.

“We’re also mixed, I have Asian ancestry myself. So we all have really different lived experiences based on our race too,” says Meza-Wong. This is why situating themselves with labels they are comfortable with is important to her.

Meza-Wong says she sees Latinx culture as largely influenced by colonization. She explains that religion and the Spanish language were tools brought forth by colonization, used to establish the current values and norms that are present in society. “Religion and language are used as forms of control to keep these systems (and) norms in place,” she says. “For people who don’t identify with either male or female, for people who are fluid, or if you’re gay or lesbian… you have a very gendered language and a very gendered society.”

Diego Aguilar Capriles is a third-year structural engineering student who identifies himself as Latino. He says the word Latinx will help people be more expressive with their sexuality, and explains that in South American culture, gender roles are very present and internalized. “(Being gay) is just not talked about, there’s a lot of hypermasculinity,” he says. Aguilar Capriles agrees that gender identity is broad and it can’t be continuously divided into two binaries like male or female. “We kind of just sweep identity under the rug, and to be able to let people know how you identify is important,” he adds. “I’m gay too, so if you have more people who are out and (you have) more awareness and conversations, I think that helps,” he says.

Although the term is still a little new to Aguilar Capriles, he says it will open people’s minds to thinking about gender in a more fluid way. “I think when you first hear it, you’re a little on the fence about it. You don’t really know what it is,” Aguilar Capriles says. “So for people who say you can’t change a language, every language has gone through change, and when we’re actually living in the time when this change is taking place, that’s when there’s a pushback.”

In South America, Aguilar Capriles says he can see Latinx used in the far future; he doesn’t think the term has really reached people back home. “It couldn’t happen the way it did here, like within a couple years it really took off,” he says, noting the way technology pushed the usage of Latinx forward. “I think internet access obviously allowed that and for a lot of South American countries, there’s not as much exposure to social media or the internet.”

Marianella Collette, a Spanish-language professor at Ryerson, was surprised when her 14-year-old son knew what Latinx was, and she didn’t. Collette suggests that the younger generation will be the ones to use Latinx and push for its establishment. She embraces the Latinx term and believes that any change in language that leads to inclusion is important.

Collette explains that there are two major movements in language – one is academia and the other is the masses. She says that academia, which refers to the structures that determine and influence language, like dictionaries or school curriculums, are usually the ones that impose new words for the public to use.

However, a lot of the time what ends up happening, she says, is that the public will change views on something, which forces academia to catch up. This fluctuation of power between academia and the public determines if and how certain words are used.

In the case of Latinx, Collette says the push is coming from members of the public seeking a term that is non-binary, for those who don’t identify as simply male or female, Latino or Latina. “It’s going to be established in English and not only with the Latino community but the LGBTQ community. That’s where I see it flourishing, because they need it and these are the people that really want it,” she says. “It’s a political and social statement.”

Collette thinks the term will continue to spread, especially among young Latinxs living in Canada or the United States. However, like Aguilar Capriles, she says she has difficulty envisioning the term being used in South America any time soon. The term Latinx originated in the north, mainly from Latinx immigrants, youth and LGBTQ folk, and she argues that South America should invent its own word for those who identify as gender-fluid. Collette says she’s also not a big fan of the “x,” and thinks it could end up sounding foreign to native Spanish speakers. But, she says there’s no real way of knowing what will happen. “Language can take any path, it can surprise you.”

In contrast to Collette, Pelkey says he likes the “x” as a gender-neutral suffix. While it’s not the only strategy for identifying non-binary people more inclusively, it’s “arguably the most powerful and the most vivid.” Pelkey explains that we contribute to changes in language every day, simply by speaking. “To speak is to choose one way of saying something over all the other similar ways of saying it,” he says. “Languages change because their speakers are collectively working to come up with better ways of solving problems.” According to Pelkey, it’s important to constantly be rethinking everyday language, as it goes a long way when it comes to solving structural and societal problems. The word Latinx is essentially a response and solution to a socio-cultural problem.

At its most basic, language is the expression and articulation of one’s thoughts and feelings to another. But it’s definitely not that simple. Language has the power to inadvertently shape our views and reflect our values as a society. “Language gives us the ability to build better models of reality,” Pelkey says.

Aguilar Capriles thinks one of the ways Latinx can be implemented into the language more naturally is by extending its reach through social media. “When people use pronouns in their social media bios, I think that’s an interesting way to say, ‘this is how I identify,’ sometimes before you even meet someone. It’s a small initiative, but I think it goes a long way,” he says.

The younger generation will largely be responsible for the future of the word, and whether it becomes more widely accepted. “(Latinx) will need to at least be legitimized by younger generation speakers, who can then pass along an affirmative attitude toward the inclusive construction to those that follow,” Pelkey says. “If that happens, the usage could become normalized within our lifetime, but that is a big if.”

Meza-Wong also sees the younger generation as more open to leading the change. She thinks it is important to challenge society’s ingrained interpretations of gender and language as a means of implementing Latinx, or any other gender-neutral term, in South America. “The main themes here are unlearn and relearn. (People) just simply being open to understanding and listening . . . because we’ve been taught certain things that aren’t necessarily good for us, or are not necessarily what we identify with,” she says. “And I think being able to use terms like this help people who don’t identify with them and helps them feel included in the language and the culture.”

Meza-Wong is confident that Latinx isn’t going anywhere. “Language has developed around culture, so the kind of language we use to describe ourselves reflects us as a people and our values.” Although Meza-Wong doesn’t like to use the word fighting, she says that’s exactly what her community must do. “We have to be willing to fight to push for this word, because it’s not going to happen overnight.”

Daniela is a fourth-year journalism student currently working as the arts and life editor.