I’m standing in a hospital hallway. My middle-aged son, Bobby, speaks in a cheerful voice with an undertone of stress to a nurse who shakes my hand and introduces herself as Barbara.

“What am I doing here?” I ask Bobby.

“We talked about this, mom,” he says. “We talked about—”

“I don’t like this place,” I whisper.

“Just give it a chance, give it a chance,” Bobby says.

“We have a lovely room picked out for you, Nina, a beautiful room,” Barbara says with a rehearsed, sympathetic smile.

“No, no,” I whimper. “I’m not going to stay here.” But they begin talking about paperwork that Bobby needs to sign as they lead me to a set of grey doors.

This is the opening scene of a virtual reality video that was showcased at an art exhibit called EMBODY – Experiencing Dementia Through New Media. The fictional video attempts to put the viewer inside the mind of someone with dementia to communicate the findings of a medical study conducted by researchers at the Toronto Rehabilitation Institute (TRI).

The exhibit was a collaborative project between Ryerson’s Daphne Cockwell School of Nursing, Ryerson’s Centre for Communicating Knowledge and TRI. By allowing the public to experience the world from the perspective of someone with dementia, the exhibit attempted to humanize dementia patients, specifically, the subjects of a study conducted by TRI researcher Dr. Andrea Iaboni. The exhibit consequently complemented the objective approach of science, which can feel detached and impersonal.

The Centre for Communicating Knowledge, an institute that helps academic research reach the public, chose artwork for the exhibit based on one of Iaboni’s studies, in which data was gathered to enable her team to pinpoint the physiological and behavioural signs that predict outbursts of agitation in dementia patients.

“Some people with dementia can experience symptoms that lead them to experience the world as frightening or stressful,” Iaboni told the Centre for Communicating Knowledge in a video. Those feelings can make people lash out, putting “themselves at risk or others around them at risk.”

Data collected from various biometric sensors — like a wristband that keeps track of one’s pulse — can go toward developing algorithms that will alert caregivers of dementia patients to an impending outburst. This can allow the caregiver to preemptively de-escalate a stressful situation. Currently, predicting agitation can be challenging, due to the difficulty that dementia patients have expressing themselves, and the subjective, sometimes biased methods that caregivers use to gauge the internal state of someone with dementia.

“This system is really about developing an objective measure of people’s behaviours,” Iaboni said.

Also on display were artistic visualizations of some of the data collected by Iaboni’s team, as well as a Snapchat filter and abstract paintings representing what it’s like to experience dementia.

Natasha Savignano, a fourth-year Ryerson nursing student who attended the exhibit, found one of the paintings particularly relevant to her experience caring for dementia patients. The painting, which spans the length of a wall, depicts a labyrinth made up of mostly black, but sometimes red and green, brushstrokes.

“I feel like navigating their thoughts is something like that,” Savignano said. “It kind of looks like an endless maze that has no objective, no reason, and is just kind of all over the place.”

Savignano said that the painting and the virtual reality video will help her take better care of people with dementia. “I feel like I always knew that’s probably what they’re thinking,” she said. But “you don’t really see it.” The lack of visible signs of distress can make busy nurses act curtly toward confused dementia patients who aren’t complying with, for example, the nurses’ requests for them to take their medication.

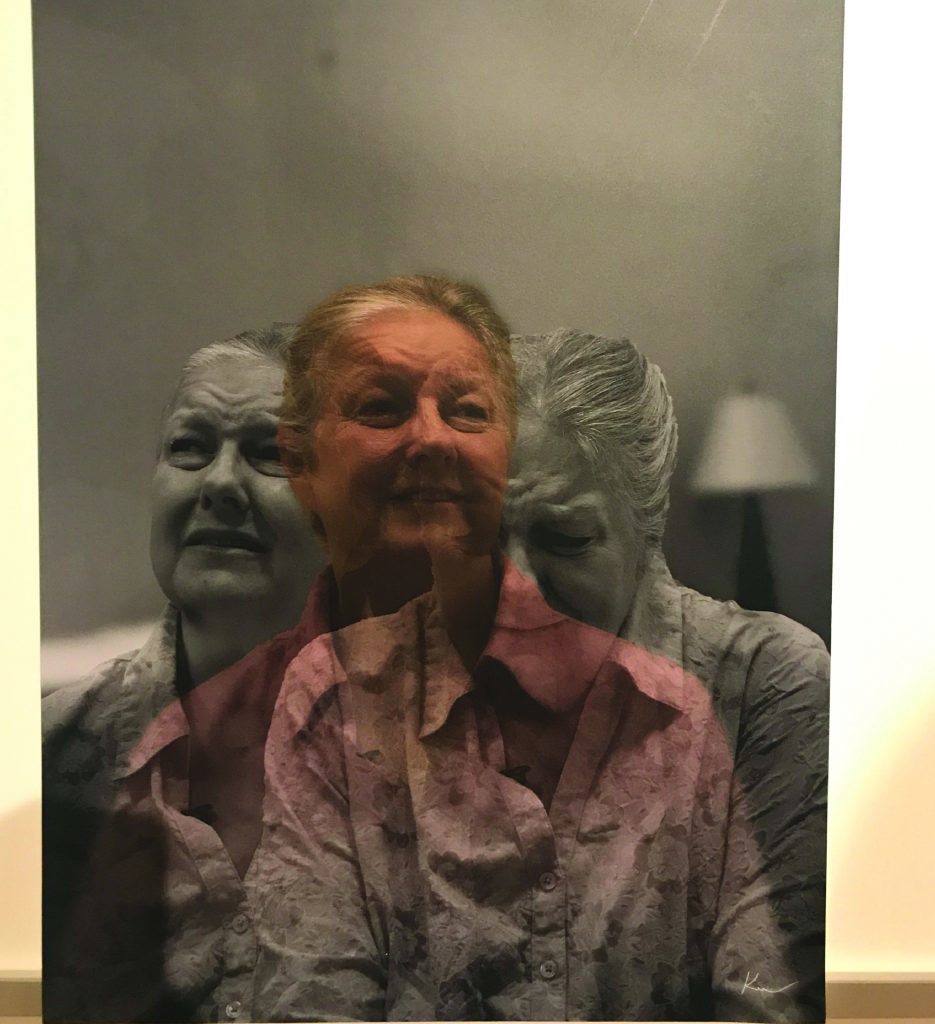

Aside from the paintings , the exhibit relied on other visual art, including photographs, to illustrate why developing a system to predict patients’ behaviours is necessary in the first place. The photographs showed two actors playing characters Charles and Nina, who represent what it’s like for men and women to experience agitation while suffering from dementia. Male patients tend to be more aggressive when agitated, while female patients tend to be more in need of support.

The photographs consisted of three translucent portraits of Nina superimposed in layers over each other. In the centre of one photograph Nina looks to the right with a small, quizzical smile. Behind that translucent image are two other grey portraits of her: one where she’s looking around, bewildered and scared, and another where she has her eyes downcast in a miserable frown. The layered photos communicate just how difficult it is for a nurse, doctor, or family member to evaluate the inner state of someone with dementia by assessing their appearance.

After going to the exhibit, Savignano said she’ll be more patient when interacting with dementia patients, and thinks all Ryerson nursing students should come to the exhibit to have a similar change of perspective. “I feel like [taking] just a little bit more time [with the patients] would be helpful, instead of getting agitated ourselves.”

“EMBODY – Experiencing Dementia Through New Media” ran from October 15 until November 9 at the Toronto Rehabilitation Institute. If you missed it, don’t worry—the exhibit will be on display again soon.