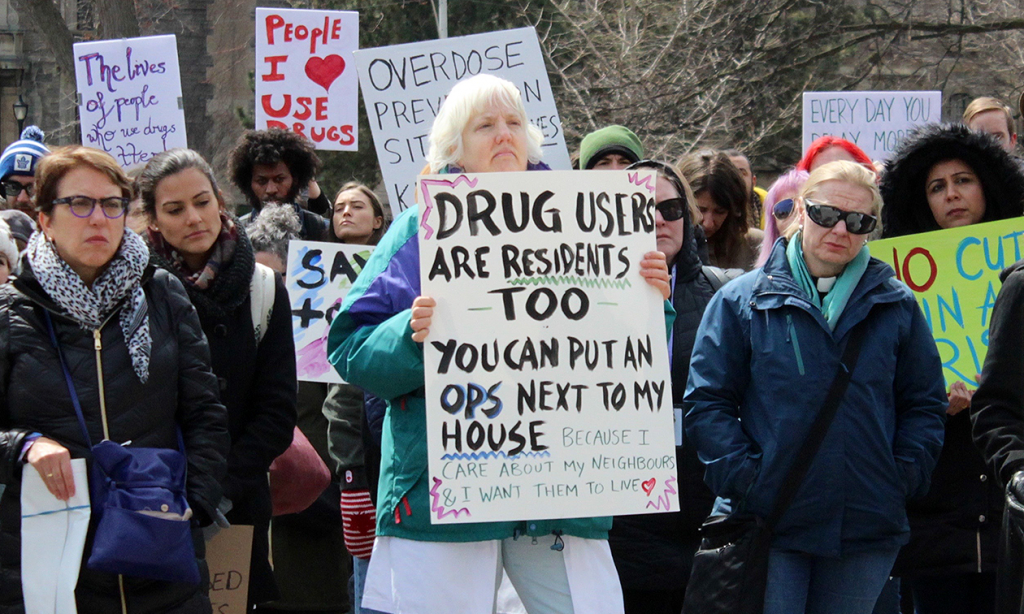

Over 100 supporters of overdose-prevention sites (OPS) took to Queen’s Park Thursday afternoon to protest provincial funding cuts to three sites across the province, including two in Toronto.

This comes after a surprise announcement March 29 from Ontario Minister of Health Christine Elliott that the province would continue to fund only 15 out of 21 sites located across Ontario. Three of them were ordered to close their doors the following Monday.

The rally was attended by workers and volunteers from Toronto sites, community members, local advocates, health-care professionals and friends and family of people who died from drug overdoses.

“It’s absolutely deplorable that in the midst of the worst public health crisis of our generation, sites are being pulled,” said Joyce Rankin, clinical manager at Street Health Toronto, one of the sites that lost funding.

She said their location at Dundas and Sherbourne streets received a last-minute exemption from the Canadian government and a grant from the federal Ministry of Health, so they could stay open.

Street Health Toronto is one of three sites that got this exemption, including St. Stephen’s Community Housing, located in Kensington Market — which also lost provincial funding — and The Works, the largest OPS in Toronto.

The Works was Toronto’s first permanent supervised injection service, and its largest. Toronto Public Health runs the location, which is situated on Dundas and Victoria streets, right next to Ryerson University. The province is currently reviewing its application for funding.

According to a statement given to the Ryersonian by the president’s office, the university became aware of The Works’ situation on Friday, following Elliott’s announcement.

Asked if the university would be involved in talks with the province on the future of The Works, president Mohamed Lachemi said he had “no idea” but would welcome the opportunity.

Overdose-prevention sites provide a multitude of services for people dealing with addiction. Many in Toronto, including Street Health Toronto, facilitate the supervised consumption of drugs at their locations.

“People are going to die with less services available,” said Rankin. “I feel that (Ontario Premier) Doug Ford and minister Elliott feel that’s an acceptable outcome. Otherwise, why would they cut the services?”

MAP: TORONTO OPS SITES, AS OF APRIL 1, 2018

Overdose prevention sites operate under the public health strategy of harm reduction: users are given clean supplies with which to consume drugs, avoiding the risk of physical harm from things like unsafe needles. Staff are available to provide overdose-reversing naloxone treatments.

The harm reduction method aims to support drug users, as opposed to criminalizing or imposing treatment upon them.

The severity of the opioid crisis has reached unprecedented levels, which advocates say makes keeping the OPS buildings open to the public more important than ever before.

According to Public Health Ontario, more than 1,200 people died from opioid-related overdoses in 2017. The number of deaths have been increasing in the province since 2003, more than doubling in number. Recent data says that more than 600 people died in the first half of 2018 alone.

Rankin said Street Health got just enough money from the federal government to stay open. On average, she said the site needs $20,000 a month to operate the OPS alone. This is for a team of one full-time co-ordinator, three part-time staff members and three release members. The centre is open for five hours a day, Monday through Friday.

Bill Sinclair is the executive director of St. Stephen’s Community Housing. He said they’re fundraising to stay open and have received dozens of donations from locals so far. According to him, they need $25,000 to operate from now until the end of April.

Sinclair said their site sees around 150 visitors a month. Since they opened last year, he said they’ve reversed around 20 overdoses. Rankin said they see 10 to 15 visitors a day, and have reversed 30 overdoses.

“We have a moral obligation to run this program,” Rankin said. “I believe that the province does not see it as an obligation to help people. We do.”